The history of the United States’ involvement in global environmental agreements is a checkered one to say the least. With this project we seek to draw back the curtain and uncover the history of corporate influence on US positions at UN negotiations. New evidence discovered by the Climate Investigations Center reveals that corporate interests, specifically petroleum, chemical and auto companies, were corrupting the US government’s approach to UN environmental initiatives going back to the first such meeting in 1972, insinuating themselves into international discussions on the impact of pollution from the very beginning, installing corporate operatives in key government positions, and designing essential aspects of the government’s approach.

The way that corporate interests, particularly fossil fuel interests, have bent, twisted, derailed and delayed UN climate negotiations has been well illuminated over past three decades. A report published last week by Global Witness, Corporate Accountability and Corporate Observatory found “636 fossil fuel lobbyists granted access to COP27,” amounting to 160 more fossil fuel lobbyists registered this year than at last year’s COP26. This and other reporting from the COP are the latest evidence of oil and gas producers’ continuing attempts to influence international climate talks. In 2019, data compiled by the Climate Investigations Center showed that fossil fuel companies and their representatives had attended the international climate negotiations process on an ongoing basis since COP1 in 1995. Years before that, the US corporate campaign group, the Global Climate Coalition, was formed in direct response to the birth of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1989, with internal budget documents showing the prioritization the GCC gave to “tracking” the IPCC.

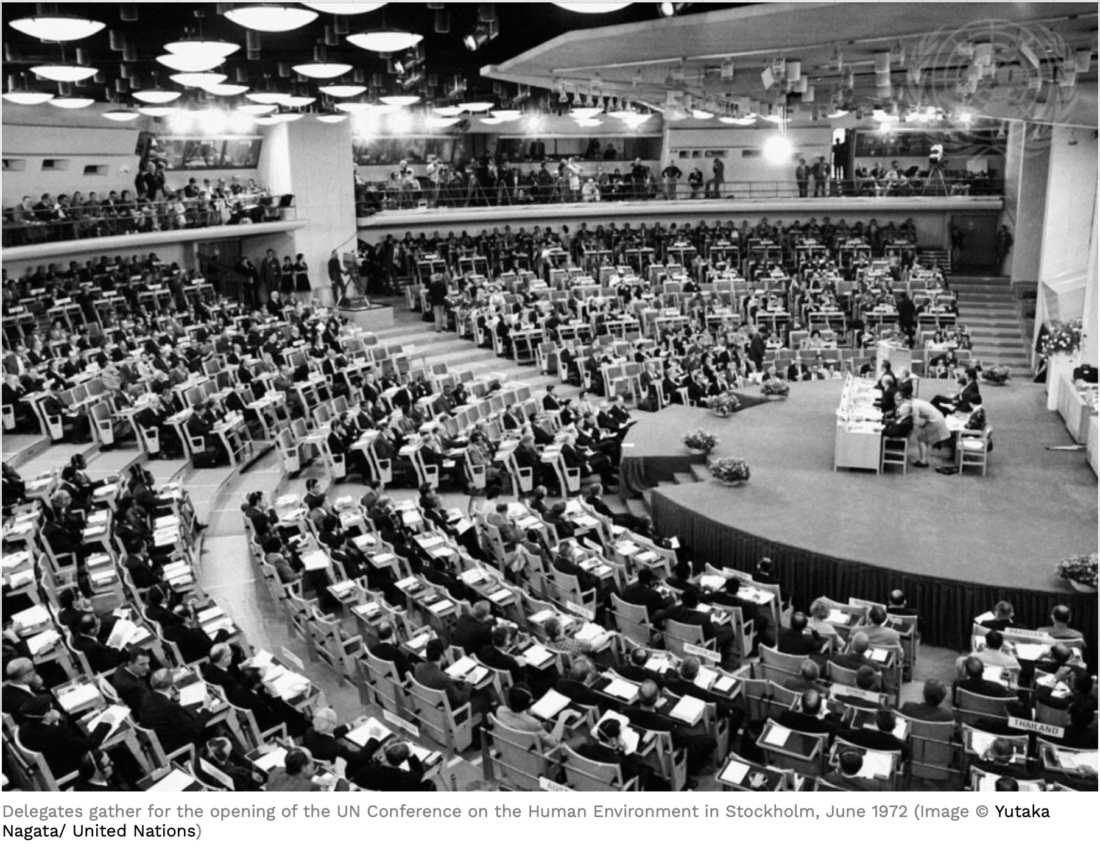

Sliding back a couple of decades earlier is eye opening. Until now, according to historic accounts, it has been believed that the US’s biggest corporate polluters were caught off-guard by and excluded from the very first UN environmental negotiations at the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) held in Stockholm, a distant precursor to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and subsequent Conference of the Parties (COP) summits.

However, newly-discovered documents show that as early as 1970, corporate interests influenced the US role in the UNCHE conference via a secretive lobbying channel built inside the US Government, within the Department of Commerce, through an advisory panel called the National Industrial Pollution Control Council (NIPCC).

The NIPCC was established by President Nixon under an Executive Order in April 1970 and its all-industry membership was composed of the CEOs, Presidents and Chairmen of the country’s most powerful companies and biggest polluters – including General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, American Motors, Exxon, Mobil, ARCO and Standard Oil of Ohio,[1]PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Monsanto, Union Carbide, Dow Chemical, Dupont and R. J. Reynolds Tobacco among many others – giving industry an active role inside the US government’s environmental decision-making at both the national and international level.

According to the documents, membership on the NIPCC gave big polluters direct access not only to the President, the Secretary of Commerce and the Head of the Council on Environmental Quality but also to the senior State Department official hand-picked by Nixon to lead US preparations for the conference.[2] Namely, Christian Herter, Jr., a former Vice President of Government Relations and Public Affairs at Mobil who was tasked with formulating the US official position presented at the UNCHE in Stockholm, pre-echoing ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson’s tenure as the Trump Administration’s Secretary of State from 2017-2018.

CIC can also reveal that, far from being excluded from UNCHE Stockholm, big polluters had inside access as members of the official US Delegation. Among the 35-member “governmental” delegation (composed mostly of top administration officials and Senators) was Frank Ikard, President of the American Petroleum Institute (API) – the oil and gas industry’s most powerful trade association and lobby group; NIPCC Chairman, Bert Cross, also Chairman of 3M[3]; and trucking magnate, John Rollins.

Christian Herter, Jr., was appointed Vice Chair of the US Delegation, with head of the brand new White House Council on Environmental Quality, Russell Train, as its Chair. According to a previously classified State Department document, it was Herter, who transmitted the U.S. Delegation’s official report of activity during the Stockholm Conference. [4]

Industry representatives also attended the Conference in an unofficial capacity, similar perhaps to today’s “observer” status used by business non-governmental organizations. These included P. N. Gammelgard, the API’s Vice President of Environmental Affairs. An additional point of intervention was found through the media tent. According to a New York Times report from Stockholm in June 1972, the “corps of 1,200 accredited “journalists” was dotted with individuals whose real connections were with corporations, rather than media.”[5] And the US wasn’t alone. A member of the Conference’s Religious Task Force, Norman J. Faramelli, also wrote that the Conference was “swarming with top level corporate executives from the US, Japan and Europe.”[6]

Key Findings

Documents discovered in CIC’s ongoing investigation show:

- The State Department actively solicited and received input from the NIPCC on international environmental issues

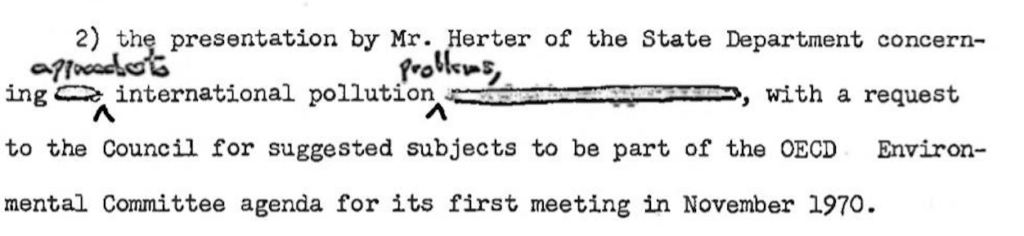

On October 14, 1970, former Mobil VP, Christian Herter, Jr., attended a meeting of the NIPCC Full Council held inside the Department of Commerce, where he made a presentation “concerning approaches to international pollution problems,” requesting that the NIPCC members suggest “subjects to be part of the OECD[7] Environmental Committee agenda for its first meeting in November 1970.”

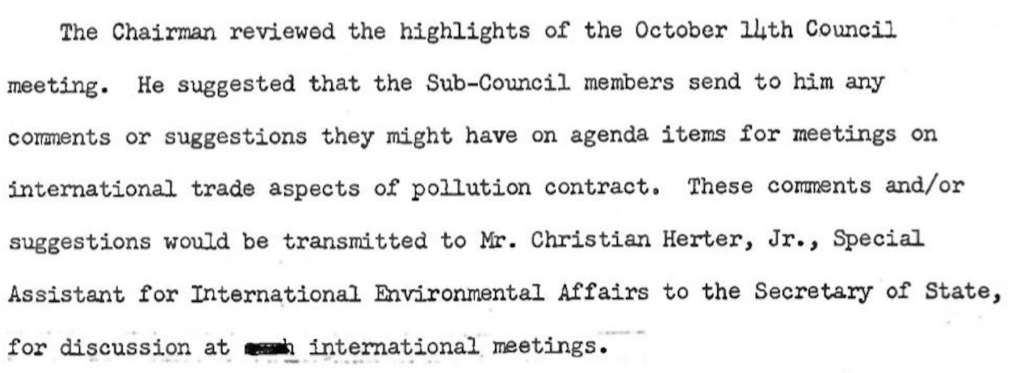

Following this presentation, industry’s “comments and suggestions” were submitted to Herter, “for discussion at international meetings.” Minutes of a December 1970 meeting of the NIPCC Chemicals Sub-Council (whose members were the President of Union Carbide, the Chairman of Monsanto, the President of Dow Chemical and the CEOs of DuPont and Mallinckrodt), record that the Sub-Council Chairman, Birny Mason Jr of Union Carbide, “suggested that the Sub-Council members send to him any comments or suggestions they might have on agenda items for meetings on international trade aspects of pollution” and stated that “these comments and/or suggestions would be transmitted to Mr Christian Herter, Jr., Special Assistant for International Environmental Affairs to the Secretary of State for discussion at international meetings.”

- Polluters established an “International Environmental Committee”

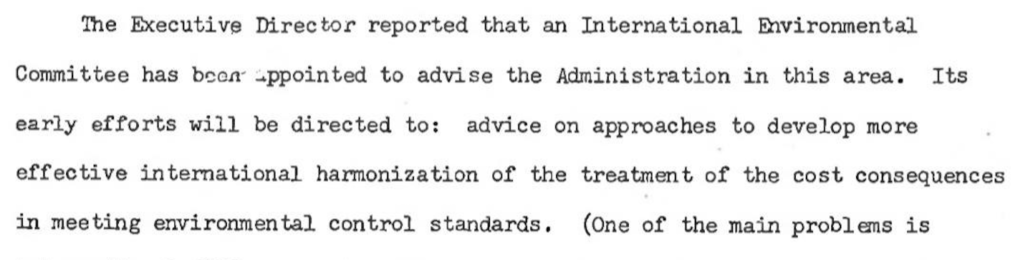

On March 26, 1971, as the date of the UN Conference drew nearer, the newly found documents reveal that the NIPCC established an all-industry “International Environmental Committee” to “advise the Administration” on “international agreements relative to environmental problems.”

Four days later, minutes of an NIPCC Chemicals Sub-Council Meeting on March 30, 1971, record that, “an International Environmental Committee has been appointed to advise the Administration in this area. Its early efforts will be directed to: advise on approaches to develop more effective international harmonization of the treatment of the cost consequences in meeting environmental control standards … and provide advice regarding the development of international agreements relative to environmental problems.”

Sound familiar?

From the very beginning, NIPCC members were in favor of ‘international harmonization” which meant opposition to any form of compensation – e.g., preferential trade deals, barriers to US businesses or other financial mechanisms – for developing countries whose rate of development would be impeded by the costs of mandatory pollution control measures. This attitude is evident in recent years in the US’s push back against a climate ‘Loss and Damage’ payment fund proposed by small island states and poorer nations to assist those who will be hardest hit by climate change but have historically contributed the least in terms of net or per capita greenhouse gas emissions.

NIPCC documents also show that leading this International Environmental Committee was Robert O. Anderson, Chairman of oil giant Atlantic Richfield Co (ARCO).[8] Anderson was also the Vice-Chair of the NIPCC’s Petroleum and Gas Sub-Council whose members included the Chairmen of Exxon Corporation, Mobil and Ashland Oil. Other members of the International Environmental Committee were V. E. Boyd, President of Chrysler; John T. Connor, Chairman of Allied Chemical; Karl R. Bendetsen, CEO of U.S. Plywood-Champion Papers, Inc.; and Ian K. MacGregor, Chairman of American Metal Climax. [9],[10]

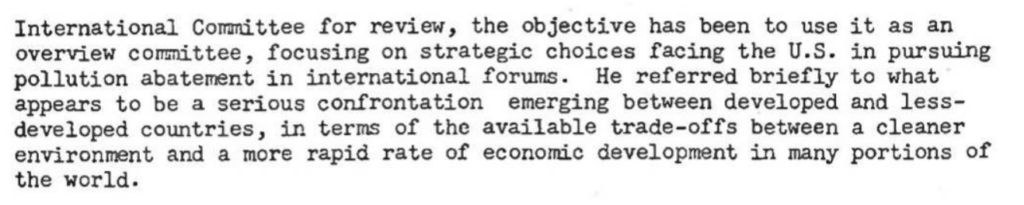

- NIPCC was an important “channel of communication” on “strategic choices” being made by the US Government.

The NIPCC was regarded by the fossil fuel industry as an important “channel of communication” with input over “the strategic choices facing the US … in international forums.”

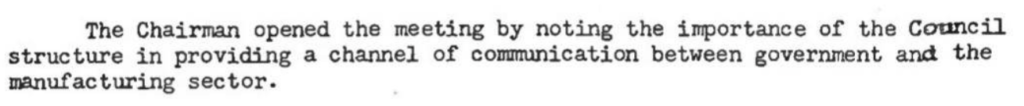

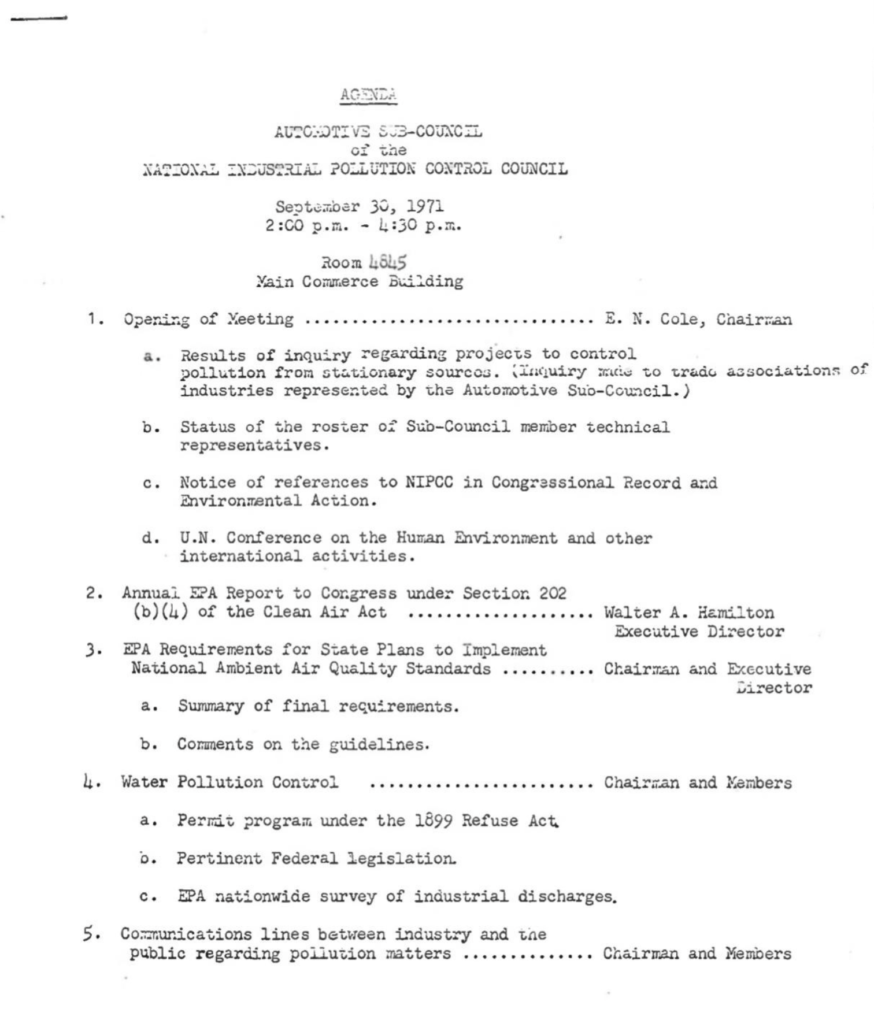

The minutes of a September 30th 1971 meeting of the NIPCC’s Automotive Sub-Council (whose members included the Presidents/CEOs/Chairmen of General Motors, Ford, Chrysler and American Motors) record that, “the Chairman (E. N. Cole, President of General Motors) opened the meeting by noting the importance of the Council structure in providing a channel of communication between government and the manufacturing sector.”

It was also noted in the minutes that NIPCC members had submitted a “large volume of detailed material” to the International Environmental Advisory Committee, prompting the NIPCC’s Executive Director Walter Hamilton, also present at the meeting, to state that the “objective” of the International Committee was to “use it as an overview committee, focusing on strategic choices facing the US in pursuing pollution abatement in international forums.”

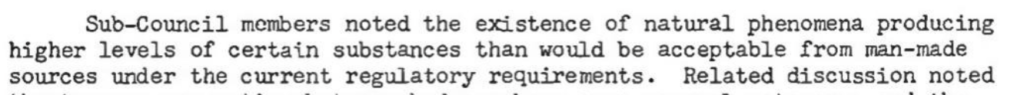

- Downplaying the significance of “man-made sources” of pollution

NIPCC minutes also reveal the general attitudes of its members to regulation. Following the discussion of the NIPCC’s influence over the US’s “strategic choices,” the minutes record the Automotive Sub-Council members attempting to downplay the significance of man-made pollution. “Sub-Council members noted the existence of natural phenomena producing higher levels of certain substances than would be acceptable from man-made sources under the current regulatory requirements.”

(A General Motors report published a few months earlier and circulated to government officials via the NIPCC, titled “AIR QUALITY STANDARDS … What Should They Be?”, had attacked existing US emissions standards on known pollutants as “overly restrictive.”)

- Industry influence over other international environmental “Advisory Committees”

The September minutes of the Automotive Sub-Council also noted that General Motors’ Cole, “opened the discussion of international activities by referring to his own membership on the US Department of State advisory committee in this area” and “distributed copies of the US National report on the Human Environment prepared for Stockholm 1972.”

In addition to his position as Chairman of the NIPCC’s Automotive Sub-Council, Cole had been appointed to the 33-member Secretary of State’s Advisory Committee on the Human Environment established in May 1971 to advise Nixon’s Secretary of State, William Rogers, on the US position at UNCHE Stockholm. This separate Advisory Committee also included Christian Herter, Jr., John Harper (Chairman, ALCOA), Charles Luce (Chairman of Utilities giant Consolidated Edison), Aubrey Wagner (Chairman, Texas Valley Authority) and Robert O. Anderson (Atlantic Richfield).

The minutes also identify V. E. Boyd (President of Chrysler) as a member of “the NIPCC’s International Environmental Advisory Committee” and record that fellow Committee members had been appointed to other bilateral advisory committees created by the Council on Environmental Quality “dealing with Canada, Mexico and Japan.”

- “Massive Industry / Government Collaboration is urgently needed”

For over fifty years, the biggest polluters have argued that they must be part of the solution to international environmental problems. Today industry-favored ‘solutions’ take the form of unenforceable net-zero emissions targets and unproven technological fixes such as Carbon Capture and Storage, Hydrogen and Geo-engineering instead of mandatory emissions-reductions programs and the phaseout of fossil fuels.

NIPCC documents reveal that big corporate polluters used the NIPCC and other means to frame industry as part of the international environmental solution as early as 1971. In February of that year, the NIPCC personally delivered its first ‘Report’ to President Nixon, as part of an “all-day meeting in Washington” attended by “200 of the nation’s top corporate heads,” including “luncheon at the State Department” and several useful PR photo opportunities.

This NIPCC report, published by the US Government Printing Office, was accessible to government officials, lawmakers, the press and the American public.

“A MASSIVE INDUSTRY/GOVERNMENT COLLABORATION IS URGENTLY NEEDED TO ASSURE THE PROMPT EFFECTIVE ACHIEVEMENT OF INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL ACCORDS,”stated the report, fully capitalized for emphasis.

Alongside this claim, the report promoted voluntary action instead of legally mandated, enforceable pollution controls. It also promoted ‘doubt’ (scientific uncertainty)over the impact of substances claimed to be damaging to the environment, elevated concerns over the economic cost of environmental measures, and argued that “environmental quality control standards” were often based on “emotional appeals … not facts.”

The report highlighted the centrality of trade in international environmental negotiations, giving it equal weight with environmental considerations: “Attention is also called to the importance of international environmental accords to prevent adverse consequences, both for environment and for trade.”

According to the NIPCC, any measures for assisting the environmentally responsible industrialization of developing countries should not be allowed to negatively impact US business interests.

What happened?

The majority of the conference’s activity focused on the future institutional frameworks that would be responsible for UN environmental initiatives and the coordination of monitoring efforts. There were no commitments to any concrete pollution reductions or specific compensation agreements for developing countries.

Explaining the US’s vote on the question of compensation, the US representative explained that “his delegation was opposed, as a matter of principle, to compensating nations for declines in their export earnings regardless of cause.”[11]

In his report on the conference, Herter, Jr., wrote “the delegation was exemplary in terms of supporting previously agreed U.S. positions on a great variety of issues.”[12]

Canada, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK also declared their opposition to compensation. France, while voting in favor, concluded that “many problems still needed to be resolved.” [13]

Writing from Stockholm, the New York Times’s special correspondent Gladwin Hill concluded, “most of the discussion was on a lofty level of international principles that will be, for the foreseeable future, entirely voluntary, that generally were quite acceptable to the United States working delegates and that are a long way from posing any problems to a manufacturer in Oshkosh, Wis.”[14]

In other words, it was an outcome that broadly suited industry very well.

In a paper for the Boston College Environment Affairs Law Review, Stockholm attendee Norman J. Faramelli speculated that “perhaps the future of the global environment will be most significantly affected by the unpublicized private meetings between American oil company officials and the delegates from the Third World nations.”[15]

Fifty-plus years on, as environmental crises loom larger, we see corporate influence has expanded in scope and influence peddlers have expanded in number.

This history lesson is part of an ongoing research project at CIC. Please contact us with any additional information you may have on this subject.

Footnotes

[1] both later part of BP America

[2] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve01/d293

[3] 3M was one of the first producers of toxic ‘forever chemicals’ PFAs

[4] Report on the UNCHE from the Vice-Chairman of Delegation (Herter) to Secretary of State Rogers, July 28, 1972, Source: National Archives, RG 59, Central Files 1970-73, SCI 42-3 UN. Confidential. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve01/d325

[5] The Pollution Lobby, Gladwin Hill, New York Times, June 18, 1972, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/06/18/archives/the-pollution-lobby-influence-peddlers-sell-little-at-meeting.html

[6] Norman J. Faramelli, Toying with the Environment and the Poor: A Report on the Stockholm Environmental Conferences, 2 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 469 (1972), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ ealr/vol2/iss3/2

[7] OECD – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

[8] ARCO was purchased by BP in 1999 for $27 Billion

[9] See Statement of Acting Executive Director, NIPCC, John L. Sullivan, p.912, in Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives, 1973, Part 5 Environmental Protection (CEQ, EPA, HUD, National Commisison on Materials Policy, NIPCC). https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Agriculture_environmental_and_Consumer_P/5i1DAQAAMAAJ?q=John+L.+Sullivan+NIPCC+Hearings+on+Agriculture&gbpv=1#f=false

[10] Federal Advisory Committees, the First Annual Report of the President to Congress, including data on individual committees (March 1973), US Senate, pp.1116-1117 (In this list of US Dept of Commerce Advisory Committees it is referred to as the International Environmental Advisory Committee) https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Federal_Advisory_Committees_First_Annual/w1O9XwXyjKAC?hl=en&gbpv=1

[11] Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, 5-16 June 1972; A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1

[12] Report on the UNCHE from the Vice-Chairman of Delegation (Herter) to Secretary of State Rogers, July 28, 1972, Source: National Archives, RG 59, Central Files 1970-73, SCI 42-3 UN. Confidential. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve01/d325

[13] Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, 5-16 June 1972; A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1, p.59

[14] The Pollution Lobby, Gladwin Hill, New York Times, June 18, 1972, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/06/18/archives/the-pollution-lobby-influence-peddlers-sell-little-at-meeting.html

[15] Norman J. Faramelli, Toying with the Environment and the Poor: A Report on the Stockholm Environmental Conferences, 2 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 469 (1972), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ ealr/vol2/iss3/2